|

Posted: 18 Nov 2015 08:13 AM PST

Posted by Victoria Strauss for Writer Beware

Recently, the New York Times published a fascinating three-part series of articles on arbitration clauses, and how such clauses "buried in tens of millions of contracts have deprived Americans of one of their most fundamental constitutional rights: their day in court." (You can also listen to an interview with the articles' author on NPR.) The articles deal mainly with consumer and employment contracts, in which, according to the Times, arbitration clauses have created "an alternate system of justice" where "rules tend to favor businesses, and judges and juries have been replaced by arbitrators who commonly consider the companies their clients." But arbitration clauses are increasingly common in publishing contracts, too--as well as in the Terms of Use of some major self-publishing platforms. And most authors don't understand their implications. What's an Arbitration Clause? Here's one example, drawn from a contract I saw recently: If any dispute shall arise between the Author and the Publisher regarding this Agreement, the Publisher and Author will first attempt to resolve such dispute through mediation, and, if that fails, such dispute shall be referred to binding arbitration in accordance with the Rules of the American Arbitration Association, and any arbitration award shall be fully enforceable as a judgment in any court of competent jurisdiction. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the parties shall have the right to conduct reasonable discovery as permitted by the arbitrator(s) and the right to seek temporary, preliminary, and permanent injunctive relief in any court of competent jurisdiction during the pendency of the arbitration or to enforce the terms of an arbitration award.They don't all include such dense legalese: Recognizing the expense, distraction, and uncertainty resulting from litigation of disputes which may arise under this Agreement, AUTHOR and PUBLISHER agree that AUTHOR and PUBLISHER shall submit any and all disputes arising in any way under this Agreement to the American Arbitration Association for final disposition in accordance with its rules.Where will you find an arbitration clause in your publishing contract? Anywhere. It may appear under a separate caption (for instance, "Arbitration and Dispute Resolution") but more often is buried under other headings, such as "Reversion and Termination" or "Miscellaneous", where it can easily be glossed over. How Arbitration Clauses Limit Your Rights Arbitration is often portrayed as an easier, more friendly method of dispute settlement, allowing the parties to avoid the hassle and expense of litigation. But as the Times points out, this reasonable-sounding explanation leaves out some darker truths.

Unfortunately, you don't have many options. It's a rare publisher that will be willing to amend its arbitration clause--let alone agree to delete it. As for Terms of Use, they are not negotiable; it's take it or leave it. Things to look for in an arbitration clause: language that ensures you can go to small claims court for qualifying amounts; that the chosen arbitrator must have publishing expertise; and that if the parties can't agree on an arbitrator within a reasonable period of time, either party can proceed to court. Be sure, also, that arbitration will be conducted by an established group, such as the American Arbitration Association. A nonprofit like the AAA is preferable to a for-profit, such as JAMS, another major arbitration firm. If your contract includes a Christian arbitration clause, see if you can get the publisher to substitute non-religious arbitration. If they refuse, seriously consider walking away. How likely is it that you'll have a legal dispute with your publisher or self-publishing service, much less cause to unite with other authors in a class action? In the general run of things, not very. But as regular readers of this blog know, you can never say never. You owe it to yourself to understand how your publishing contract, or your self-pub platform's Terms of Use, does or does not restrict your right to legal redress. |

pages

- Home

- The Adventures of Boots: The Giant Snowball (Revised, Republished, Second Edition)

- The Adventures of Boots: The Christmas Surprise

- A Porpoise for Cara

- S.T.O.P. Bullying

- My Daddy is a Star

- Chilly Willy the Hoodie Wearing Bully

- A Legend Among Us

- Sanaa: The Golden Princess

- Guest blogging on Deanie Humphrys Dunne's site tod...

- Introducing Author Jennifer Young

- Poetry

- Interview with Amberly Kristen Clowe (Krissy Clowe...

- Interview with Judy Nickles

- My media page

- More pictures from Petit Jean State Park

- PETIT JEAN STATE PARK ~ ARKANSAS

- Tips for Independent Authors

- Tips for authors

- Interesting Articles

Thursday, November 19, 2015

How about that book contract and what it really says...

Monday, October 26, 2015

National Black Book Festival 2015 in Houston

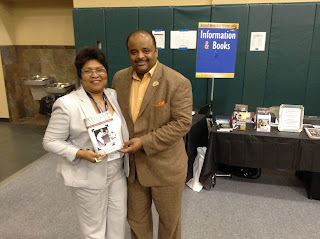

Roland Martin, News Commentator and Author

Akua Fayette

My cousin Donna Walker

My friend Alice Horton (right) and her friend

My friend Janis Kearny

With Tezlyn Figaro

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Do you think you have a legitimate reason to terminate your publisher's contract?

GETTING OUT OF YOUR BOOK CONTRACT (MAYBE)

Posted by Victoria Strauss for Writer Beware

Writer Beware often hears from authors who've signed up with bad or inexperienced or dishonest publishers, and are desperate to get free. They write to us wanting to know how they can break their contracts and regain their rights. Unfortunately, there's usually no easy answer to this question, even where the publisher has clearly breached its contractual obligations. Too often, I have to tell people that they are probably stuck.

That said, here are some general suggestions, which may or may not be applicable to your situation, and may or may not work for you (obligatory disclaimer: I'm not a lawyer, so what follows should not be construed as legal advice).

1. First and most obvious, check your contract for a termination clause. If there is one, invoke it per the instructions. Beware, though, of termination fees, which some publishers use as a way to make a quick buck off the back end.

2. If there's no termination clause, try approaching the publisher and simply asking to be released. A publisher may refuse or ignore such a request--but sometimes it will recognize that an unhappy author isn't an asset, and may be willing to let him or her go.

If you take this approach, don't dwell on the problems you've had with the publisher. Try to keep your explanations as neutral as possible--such as saying that you don't feel you have the time or resources to help promote your book, or pointing to falling sales. If you feel you must mention problems, do so in a factual, businesslike manner, without recriminations or accusations. Especially, don't mention any negative information you may have found online or heard from other authors. As large a part as this may play in your desire to be free, your request is about you and your book, not other authors and their books. Bringing others' complaints into the picture is likely to alienate or anger the publisher, in which case it may be much less disposed to pay attention to your request. (In some cases, it may become twice as determined to hold on to you.)

Another thing not to do: informing the publisher that it's in breach, and that you're terminating the contract yourself. This doesn't work for two reasons. First, even if you're correct and the publisher has breached its obligations--and even if the contract includes a provision for termination due to the publisher's breach, which not all contracts do--you, personally, have no way to enforce a termination. The publisher can simply deny your allegations, or stick its metaphorical fingers in its metaphorical ears and go right on producing and selling your book.

Second, you may consider the contract to be null and void, and your current publisher may not have the resources to sue you if it disagrees--but if you want to re-publish, you'll have problems. Another publisher won't be interested in a book whose rights aren't unambiguously free and clear. Even self-publishing services require you to warrant that you have the right to publish.You must be able to show some kind of formal rights reversion document--which you won't be able to do unless your publisher actually consents to let you go.

Once again, watch out for demands for money. I've heard from some writers whose publishers attempted to blackmail them into paying a fee when they requested release, and from others whose publishers required a sizeable termination fee even though no fee was mentioned in the contract.

3. If you're a member of a writers' group, they may be able to help. For instance, SFWA has Griefcom, which will directly intercede in an attempt to resolve the situation for you. Similar services are provided by the National Writers Union's Grievance Assistance program. Novelists Inc. has a legal fund, which entitles members to up to two billable hours of legal consultation per year.

4. If there's no termination clause and the publisher refuses to consider a release request, you can resign yourself to waiting things out, either to the end of the contract term, if the contract is time-limited, or until the publisher declares your book out of print. Obviously this is more feasible for relatively brief terms of one to three years, and less so for longer terms, or for life-of-copyright contracts--especially since so much publishing now is digitally-based, and with digital publishing there's little incentive for publishers to take works out of print. Depending on your situation and your finances, however, it may still be preferable to the final option....

5. Consult legal counsel about your situation, and your options for taking legal action. This is where the issue of breach becomes relevant. A publisher may ignore an author's personal claims of breach, but may pay more attention if an attorney is involved.

If you choose this option, not just any lawyer will do. You want someone who practices publishing law. Publishing is a complicated business, with practices and conventions that are not well-understood by people in other fields; and publishing contracts are unique documents with terms and conditions that aren't found elsewhere. In order to provide effective representation, your lawyer needs the appropriate skill- and knowledge-set.

(This same caution, by the way, applies to hiring a lawyer to vet a publishing contract prior to signing it. I hear from any number of writers whose non-publishing-specialist lawyers gave the green light to a contract that would never have passed muster with a publishing law specialist, or a competent literary agent.)

There are a number of options for low-cost legal services, some of them specifically for people in the creative arts. For instance, many US states have Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts organizations, which provide services geared to helping people who work in the arts. The Arts Law Centre of Australia provides free- or low-cost legal advice and referrals for Australian creators and arts organizations. Artists’ Legal Advice Service helps creators who are residents of Ontario, Canada. Artists’ Legal Outreach does the same for residents of British Columbia, and similar assistance is provided in Montreal by the Montreal Artists’ Legal Clinic. There are also general referral services, such as the American Bar Association Lawyer Referral Network.

You can find more information and links on the Legal Recourse page of Writer Beware.

Writer Beware often hears from authors who've signed up with bad or inexperienced or dishonest publishers, and are desperate to get free. They write to us wanting to know how they can break their contracts and regain their rights. Unfortunately, there's usually no easy answer to this question, even where the publisher has clearly breached its contractual obligations. Too often, I have to tell people that they are probably stuck.

That said, here are some general suggestions, which may or may not be applicable to your situation, and may or may not work for you (obligatory disclaimer: I'm not a lawyer, so what follows should not be construed as legal advice).

1. First and most obvious, check your contract for a termination clause. If there is one, invoke it per the instructions. Beware, though, of termination fees, which some publishers use as a way to make a quick buck off the back end.

2. If there's no termination clause, try approaching the publisher and simply asking to be released. A publisher may refuse or ignore such a request--but sometimes it will recognize that an unhappy author isn't an asset, and may be willing to let him or her go.

If you take this approach, don't dwell on the problems you've had with the publisher. Try to keep your explanations as neutral as possible--such as saying that you don't feel you have the time or resources to help promote your book, or pointing to falling sales. If you feel you must mention problems, do so in a factual, businesslike manner, without recriminations or accusations. Especially, don't mention any negative information you may have found online or heard from other authors. As large a part as this may play in your desire to be free, your request is about you and your book, not other authors and their books. Bringing others' complaints into the picture is likely to alienate or anger the publisher, in which case it may be much less disposed to pay attention to your request. (In some cases, it may become twice as determined to hold on to you.)

Another thing not to do: informing the publisher that it's in breach, and that you're terminating the contract yourself. This doesn't work for two reasons. First, even if you're correct and the publisher has breached its obligations--and even if the contract includes a provision for termination due to the publisher's breach, which not all contracts do--you, personally, have no way to enforce a termination. The publisher can simply deny your allegations, or stick its metaphorical fingers in its metaphorical ears and go right on producing and selling your book.

Second, you may consider the contract to be null and void, and your current publisher may not have the resources to sue you if it disagrees--but if you want to re-publish, you'll have problems. Another publisher won't be interested in a book whose rights aren't unambiguously free and clear. Even self-publishing services require you to warrant that you have the right to publish.You must be able to show some kind of formal rights reversion document--which you won't be able to do unless your publisher actually consents to let you go.

Once again, watch out for demands for money. I've heard from some writers whose publishers attempted to blackmail them into paying a fee when they requested release, and from others whose publishers required a sizeable termination fee even though no fee was mentioned in the contract.

3. If you're a member of a writers' group, they may be able to help. For instance, SFWA has Griefcom, which will directly intercede in an attempt to resolve the situation for you. Similar services are provided by the National Writers Union's Grievance Assistance program. Novelists Inc. has a legal fund, which entitles members to up to two billable hours of legal consultation per year.

4. If there's no termination clause and the publisher refuses to consider a release request, you can resign yourself to waiting things out, either to the end of the contract term, if the contract is time-limited, or until the publisher declares your book out of print. Obviously this is more feasible for relatively brief terms of one to three years, and less so for longer terms, or for life-of-copyright contracts--especially since so much publishing now is digitally-based, and with digital publishing there's little incentive for publishers to take works out of print. Depending on your situation and your finances, however, it may still be preferable to the final option....

5. Consult legal counsel about your situation, and your options for taking legal action. This is where the issue of breach becomes relevant. A publisher may ignore an author's personal claims of breach, but may pay more attention if an attorney is involved.

If you choose this option, not just any lawyer will do. You want someone who practices publishing law. Publishing is a complicated business, with practices and conventions that are not well-understood by people in other fields; and publishing contracts are unique documents with terms and conditions that aren't found elsewhere. In order to provide effective representation, your lawyer needs the appropriate skill- and knowledge-set.

(This same caution, by the way, applies to hiring a lawyer to vet a publishing contract prior to signing it. I hear from any number of writers whose non-publishing-specialist lawyers gave the green light to a contract that would never have passed muster with a publishing law specialist, or a competent literary agent.)

There are a number of options for low-cost legal services, some of them specifically for people in the creative arts. For instance, many US states have Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts organizations, which provide services geared to helping people who work in the arts. The Arts Law Centre of Australia provides free- or low-cost legal advice and referrals for Australian creators and arts organizations. Artists’ Legal Advice Service helps creators who are residents of Ontario, Canada. Artists’ Legal Outreach does the same for residents of British Columbia, and similar assistance is provided in Montreal by the Montreal Artists’ Legal Clinic. There are also general referral services, such as the American Bar Association Lawyer Referral Network.

You can find more information and links on the Legal Recourse page of Writer Beware.

Tuesday, August 4, 2015

Saturday, July 25, 2015

The history of the Swastika: Good not evil

In ancient times, the symbol of the swastika meant good, until it was stolen by Hitler, like most good things. It was one bad man's adoption of the word that changed the meaning of it.

http://www.ancient-origins.net/

When Adolph Hitler, the frustrated artist, was placed in charge of propaganda for the fledgling National Socialist Party in 1920, he realized that the party needed a vivid symbol to distinguish it from rival groups. He sought a design, therefore, that would attract the masses. Hitler selected the swastika as the emblem of racial purity displayed on a red background “to win over the worker,”

When Adolph Hitler, the frustrated artist, was placed in charge of propaganda for the fledgling National Socialist Party in 1920, he realized that the party needed a vivid symbol to distinguish it from rival groups. He sought a design, therefore, that would attract the masses. Hitler selected the swastika as the emblem of racial purity displayed on a red background “to win over the worker,”

Return to The Holocaust Education Program Resource Guide

http://www.ancient-origins.net/

The Swastika: A Sign of Good Luck Becomes a Symbol of Evil

Pages 14-15

The Swastika Flag

The swastika is a very old symbol with use widespread throughout the world. Sometimes referred to as a “Gammadion” “Hakenkreuz” or a “Flyfot,” it traditionally had been a sign of good fortune and well being The word “swastika” is derived from the Sanskrit “su” meaning “well” and “asti” meaning “being.” It also is considered to be a representation of the sun and is associated with the worship of Aryan sun gods. It is a symbol in both Jainism and Buddhism, as well as a Nordic runic emblem and a Navajo sign.

By definition, the swastika is a primitive symbol or ornament in the form of a cross. As the illustration below shows, the arms of the cross are of equal length with a section of each arm projecting at right angles from the end of each arm, all in the same direction and usually clockwise.

Hitler had a convenient but spurious reason for choosing the Hakenkreuz or hooked cross. It had been used by the Aryan nomads of India in the Second Millennium B.C. In Nazi theory, the Aryans were the Germans ancestors, and Hitler concluded that the swastika had been “eternally anti-Semitic.”

In spite of its fanciful origin the swastika flag was a dramatic one and it achieved exactly what Hitler intended from the first day it was unfurled in public. Anti-Semites and unemployed workers rallied to the banner, and even Nazi opponents were forced to acknowledge that the swastika had a “hypnotic effect.”

“The hooked cross” wrote American correspondent William Shirer “seemed to beckon to action the insecure lower-middle classes which had been floundering in the uncertainty of the first chaotic postwar years.” The swastika flag had a suggestive sense of power and direction. It embodied all of the Nazi concepts within simple symbol. As Adolph Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf, “In red we see the social idea of the movement, in white the Nationalist idea, and in the swastika the vision of’ the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man.”

The Bremen Incident

One of the first actions Hitler carried or after becoming Chancellor in 1933 was to abolish the Weimar Republic flag. On April 22, 1933 he decreed that the national flags of German would be the old Imperial red, white, and black tricolor and flown in conjunction with the swastika flag. These flags were to be flown together on all merchant ships, which led to a serious incident with diplomatic consequences.

On the night of Friday, July 26, 1935, several hundred Communists took part in an anti Nazi demonstration on a pier in New York harbor as the German liner Bremen was about to depart for Europe. They attempted to board the liner and were fought by 250 policemen, detectives, and crew members. Thirty of the demonstrators gained the forelock of the vessel and tore down the swastika flag flying there and threw it into the Hudson River. In the short fierce struggle with the police, a detective was badly beaten before the Communists were ejected.

Meanwhile, there was savage fighting on the pier and in the adjacent streets. The police used their batons freely on the heads of the Communists and after a time the demonstrators we drawn off. The police arrested four men alleged to be the assailants of the injured detective. Three others were arrested for disorderly conduct.

The injured detective and two of the rioters were taken to the hospital. Ten of the Bremen’s crew also were treated for cuts and bruises. The liner departed on time, and 20 policemen sailed with her as far as the quarantine station to guard against the possibility that other Communists might be concealed on board and start a new attack. The Bremen’s commander, Captain Ziegenbein, commended the police’s work. The police officials, however, blamed the ship’s officers for taking too lightly a warning they had sent them hours before the riot occurred.

The indignities inflicted upon the German flag by the American anti-Nazi demonstrators on board the Bremen resulted four days later in an emphatic protest being delivered to the American Acting Secretary of State by the German Charge d’Affaires in Washington. It was pointed out to the German diplomat, however, that the insult had been aimed at the “Party” flag and that the National flag had not been interfered with: a very fine distinction in the circumstances but one which precipitated the Nuremberg Flag Laws of September 15, 1935.

The whole question of the German National flag was resolved seven weeks later during the Seventh Reichsparteitag Congress held at Nuremberg in September 1935. This annual occasion was used by Hitler to publicly announce that the red, white, and black swastika flag of the Nazi Party would henceforth be the National flag of Germany. The incentive to solve the unsatisfactory arrangement of flying two flags together representing the nation had been thrust upon the Fuhrer as a direct result of the Bremen incident. The official use of the swastika flag came simultaneously with the increased use of racial policies.

The Swastika Flag’s use as the National Flag was a symbol of the acceleration of the Nazi’s anti-Semitic agenda which included the September 15, 1936, “Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor.” These laws revoked the Jews’ citizenship in the Reich. Jews could not vote, marry Aryans, or employ “in domestic service, female subjects of German or kindred blood who are under the age of 45 years.”

Jews found themselves excluded from schools, libraries, theaters, and public transpor-tation facilities- Passports were stamped with the word “Jew.” Name changes were disallowed, but Jewish men had to add the middle name “Israel,” Jewish women the name “Sarah.” Jewish wills that offended the “sound judgement of the people” could be legally voided. Furthermore, Jewish businesses were taken away from their owners and placed in the hands of German “trustees.”

The Bremen Incident led the Nazi’s to raise their banner of hatred as a national symbol while making the Jews into “second class subjects” of Germany. The Jews were then treated as the untermenschenHitler believed they were.

TABLE of CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION AND PROGRAM GOALS

- HOLOCAUST BACKGROUND INFORMATION HOLOCAUST CHRONOLOGY

- ADOLF HITLER: A STUDY IN TYRANNY

- THE SWASTIKA: A SIGN OF GOOD LUCK BECOMES A SYMBOL OF EVIL

- LEBENSRAUM: LIVING SPACE FOR THE GERMAN RACE

- TRANSLATION OF A PROPERTY CONFISCATION ORDER

- AUSCHWITZ: THE CAMP OF DEATH

- “OH, NO, IT CAN’T BE”

- IN THE LIBERATED CAMPS

- PURSUING THE KILLERS

- EUROPE’S DISPLACED MILLIONS

- VOCABULARY LIST

- QUESTIONS ON HITLER

- SWASTIKA QUESTIONS

- AUSCHWITZ QUESTIONS

- OH, NO, IT CAN’T BE – QUESTIONS

- THINKING IT OVER

- HOLOCAUST VIDEOGRAPHY

- HOLOCAUST BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tuesday, July 7, 2015

AWC

Ome year ago the Arkansas Pioneer Branch of NLAPW (National League of American Pen Women) celebrated our 70th Anniversary and one of our very special guests was our distinguished Govenor Mike Beebe.

Chilly Willy the Hoodie Wearing Bully

http://www.amazon.com/Linda-Black/e/B0056C44X6/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0

Bullying is a great problem and seems to be getting worse. Do you know a bully? Have you ever been bullied or have you been a bully.? Did you know that 70% of school age children report some form of bullying, with verbal being the most prevalent, and a stunning 14% of bullying among students are violent cases? A huge percentage of students miss school everyday because they are afraid because of bullying.

Check out my newest book, a narrative about young lad who was a big time bully.

Bullying is a great problem and seems to be getting worse. Do you know a bully? Have you ever been bullied or have you been a bully.? Did you know that 70% of school age children report some form of bullying, with verbal being the most prevalent, and a stunning 14% of bullying among students are violent cases? A huge percentage of students miss school everyday because they are afraid because of bullying.

Check out my newest book, a narrative about young lad who was a big time bully.

Tuesday, June 9, 2015

Monday, May 25, 2015

Ever wondered how to get reversion rights from your publisher? Here's a very good article:

HOW TO REQUEST RIGHTS REVERSION FROM YOUR PUBLISHER

Posted by Victoria Strauss for Writer Beware

Partly in connection with the controversy surrounding troubled publisher Ellora's Cave, I've been getting questions about how to go about requesting rights reversion from one's publisher.

There's no official format for a rights reversion request, and if you do a websearch on "rights reversion request" you can find various pieces of advice from authors and others. Here's the procedure I'd suggest. (Note that I'm not a lawyer, so this is not legal advice.)

First of all, if you have a competent agent, ask your agent to handle it. Especially if you're with a larger publisher, your agent is more likely to know exactly whom to contact, and in a better position to push for a response.

If you don't have an agent, or if your agent is not very competent or not very responsive:

1. Look through your contract to find the rights reversion or termination language. Sometimes this is a separate clause; sometimes it's included in other clauses. See if there are stipulations for when and how you can request your rights back. For example, a book may become eligible for rights reversion once sales numbers or sales income fall below a stated minimum.

The ideal reversion language is precise ("Fewer than 100 copies sold in the previous 12 consecutive months") and makes reversion automatic on request, once stipulations are fulfilled. Unfortunately, reversion language is often far from ideal. Your contract may impose a blackout period (you can't request reversion until X amount of time after your pub date), a waiting period after the reversion request (the publisher has X number of months to comply, during which time your book remains on sale), or provide the publisher with an escape mechanism (it doesn't have to revert if it publishes or licenses a new edition within 6 months of your request).

Worse, your contract may not include any objective standards for termination and reversion, leaving the decision entirely to the publisher's discretion; or it may include antiquated standards ("The book shall not be considered out of print as long as it is available for sale through the regular channels of the book trade"--meaningful in the days when books were physical objects only and print runs could be exhausted, but useless for today's digital reality).

It's also possible that your contract may not include any reversion language at all. This is often the case with limited-term contracts, so if your contract is one of those, you may just have to wait things out. Unfortunately, I've also seen life-of-copyright contracts with no reversion language. This is a big red flag: a life-of copyright contract should always be balanced with precise reversion language.

2. Begin your reversion request by stating your name, the title(s) of your book(s), your pub date(s), and your contract signing date(s). I don't think there's any need to create separate requests if you're requesting reversion on more than one book; but there are those who disagree.

3. If you do meet your contract's reversion stipulations, indicate how you do ("Between August 1, 2013 and July 31, 2014, Title X sold 98 copies") and state that per the provisions of your contract, you're requesting that your rights be reverted to you. If the contract provides a specific procedure for making the reversion request, follow this exactly.

4. If you don't meet your contract's reversion stipulations, if reversion is at the publisher's discretion, or if your contract has no reversion language, simply request that the publisher terminate the contract and return your rights to you. If there's an objective reason you can cite--low sales, for instance, or your own inability to promote the book--do so, even if those reasons are not mentioned in the contract as a condition of reversion.

5. DO: be polite, businesslike, and succinct.

6. DON'T: mention the problems the publisher may be having, the problems you've had with the publisher, problems other authors have had, online chatter, news coverage, lawsuits, or anything else negative. As much as you may be tempted to vent your anger, resentment, or fear, rubbing the publisher's nose in its own mistakes amd failures will alienate it, and might cause it to decide to punish you by refusing your request or just refusing to respond. Again: keep it professional and businesslike.

7. Request that the publisher provide you with a reversion letter. Certain contract provisions (such as the author's warranties) and any outstanding third-party licenses will survive contract termination. Also, publishers typically claim copyright on cover art and on a book's interior format (i.e., you couldn't just re-publish a scanned version of the book), and the right to sell off any printed copies that exist at the time of reversion (with royalties going to you as usual). Some publishers are starting to claim copyright on metadata (which they define not just as ISBNs and catalog data, but back cover copy and advertising copy).

I've also seen publishers claim copyright on editing (which means they'd revert rights only to the originally-submitted manuscript). This is ridiculous and unprofessional. For one thing, it provides no benefit to the publisher--what difference does it make if an author re-publishes the final version of a book from which the publisher has already received the first-rights benefit? For another, if edits are eligible for copyright at all, copyright would belong to the editor, not the publisher. If you find a copyright claim on editing in a publishing contract, consider it a red flag. If the publisher makes this claim without a contractual basis--as some publishers do--feel free to ignore it.

To give you an idea of what an official reversion letter looks like, here's a screenshot of one of mine.

8. If the publisher registered your copyright, ask for the original certificate of copyright. Smaller publishers often don't register authors' copyrights--again, check your contract, and double-check by searching on your book at the US Copyright Office's Copyright Catalog.

9. Send the request by email and, if you have the publisher's physical address, by snail mail, return receipt requested.

Hopefully your publisher will comply with your reversion request. But there are many ways in which a publisher can stall or dodge, from claiming that your records are wrong to simply not responding. If that happens, there's not much you can do, apart from being persistent, or deciding to take legal action--though that's an expensive option.

One last thing: a publisher should not put a price on rights reversion. Charging a fee for reversion or contract termination is a nasty way for a publisher to make a quick buck as a writer goes out the door. A termination fee in a publishing contract is a red flag (for more on why, see my blog post). And attempting to levy a fee that's notincluded in the contract is truly disgraceful.

Partly in connection with the controversy surrounding troubled publisher Ellora's Cave, I've been getting questions about how to go about requesting rights reversion from one's publisher.

There's no official format for a rights reversion request, and if you do a websearch on "rights reversion request" you can find various pieces of advice from authors and others. Here's the procedure I'd suggest. (Note that I'm not a lawyer, so this is not legal advice.)

First of all, if you have a competent agent, ask your agent to handle it. Especially if you're with a larger publisher, your agent is more likely to know exactly whom to contact, and in a better position to push for a response.

If you don't have an agent, or if your agent is not very competent or not very responsive:

1. Look through your contract to find the rights reversion or termination language. Sometimes this is a separate clause; sometimes it's included in other clauses. See if there are stipulations for when and how you can request your rights back. For example, a book may become eligible for rights reversion once sales numbers or sales income fall below a stated minimum.

The ideal reversion language is precise ("Fewer than 100 copies sold in the previous 12 consecutive months") and makes reversion automatic on request, once stipulations are fulfilled. Unfortunately, reversion language is often far from ideal. Your contract may impose a blackout period (you can't request reversion until X amount of time after your pub date), a waiting period after the reversion request (the publisher has X number of months to comply, during which time your book remains on sale), or provide the publisher with an escape mechanism (it doesn't have to revert if it publishes or licenses a new edition within 6 months of your request).

Worse, your contract may not include any objective standards for termination and reversion, leaving the decision entirely to the publisher's discretion; or it may include antiquated standards ("The book shall not be considered out of print as long as it is available for sale through the regular channels of the book trade"--meaningful in the days when books were physical objects only and print runs could be exhausted, but useless for today's digital reality).

It's also possible that your contract may not include any reversion language at all. This is often the case with limited-term contracts, so if your contract is one of those, you may just have to wait things out. Unfortunately, I've also seen life-of-copyright contracts with no reversion language. This is a big red flag: a life-of copyright contract should always be balanced with precise reversion language.

2. Begin your reversion request by stating your name, the title(s) of your book(s), your pub date(s), and your contract signing date(s). I don't think there's any need to create separate requests if you're requesting reversion on more than one book; but there are those who disagree.

3. If you do meet your contract's reversion stipulations, indicate how you do ("Between August 1, 2013 and July 31, 2014, Title X sold 98 copies") and state that per the provisions of your contract, you're requesting that your rights be reverted to you. If the contract provides a specific procedure for making the reversion request, follow this exactly.

4. If you don't meet your contract's reversion stipulations, if reversion is at the publisher's discretion, or if your contract has no reversion language, simply request that the publisher terminate the contract and return your rights to you. If there's an objective reason you can cite--low sales, for instance, or your own inability to promote the book--do so, even if those reasons are not mentioned in the contract as a condition of reversion.

5. DO: be polite, businesslike, and succinct.

6. DON'T: mention the problems the publisher may be having, the problems you've had with the publisher, problems other authors have had, online chatter, news coverage, lawsuits, or anything else negative. As much as you may be tempted to vent your anger, resentment, or fear, rubbing the publisher's nose in its own mistakes amd failures will alienate it, and might cause it to decide to punish you by refusing your request or just refusing to respond. Again: keep it professional and businesslike.

7. Request that the publisher provide you with a reversion letter. Certain contract provisions (such as the author's warranties) and any outstanding third-party licenses will survive contract termination. Also, publishers typically claim copyright on cover art and on a book's interior format (i.e., you couldn't just re-publish a scanned version of the book), and the right to sell off any printed copies that exist at the time of reversion (with royalties going to you as usual). Some publishers are starting to claim copyright on metadata (which they define not just as ISBNs and catalog data, but back cover copy and advertising copy).

I've also seen publishers claim copyright on editing (which means they'd revert rights only to the originally-submitted manuscript). This is ridiculous and unprofessional. For one thing, it provides no benefit to the publisher--what difference does it make if an author re-publishes the final version of a book from which the publisher has already received the first-rights benefit? For another, if edits are eligible for copyright at all, copyright would belong to the editor, not the publisher. If you find a copyright claim on editing in a publishing contract, consider it a red flag. If the publisher makes this claim without a contractual basis--as some publishers do--feel free to ignore it.

To give you an idea of what an official reversion letter looks like, here's a screenshot of one of mine.

8. If the publisher registered your copyright, ask for the original certificate of copyright. Smaller publishers often don't register authors' copyrights--again, check your contract, and double-check by searching on your book at the US Copyright Office's Copyright Catalog.

9. Send the request by email and, if you have the publisher's physical address, by snail mail, return receipt requested.

Hopefully your publisher will comply with your reversion request. But there are many ways in which a publisher can stall or dodge, from claiming that your records are wrong to simply not responding. If that happens, there's not much you can do, apart from being persistent, or deciding to take legal action--though that's an expensive option.

One last thing: a publisher should not put a price on rights reversion. Charging a fee for reversion or contract termination is a nasty way for a publisher to make a quick buck as a writer goes out the door. A termination fee in a publishing contract is a red flag (for more on why, see my blog post). And attempting to levy a fee that's notincluded in the contract is truly disgraceful.

Sunday, May 17, 2015

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Tucson Book Festival

It's that time folks! The weather is going to be gorgeous. Come out and join me at booth # 214 today March 14 and tomorrow March 15, mention where you saw my post and get a little extra something something! See ya there!

Monday, February 16, 2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)